Mission Possible, But Very Unlikely

What we discovered while looking for a species once considered extinct

We wonder what it’s like being one of the last remaining members of a species. Does the last remaining northern white rhino or black footed ferret on Earth understand that fact, or even just how rare they are? Do they feel a sense of sorrow or existential dread when they look around and see no creature that looks like them? Do they feel lonely without anyone to hunt, mate, or forage with? Do they feel pressure to survive and procreate? Do they understand on any level that when they are pronounced dead, the magnitude far exceeds a single organic life form returning to the Earth? It’s a fascinating thought exercise with few answers. What we do know is that when that creature dies, in that instant, hundreds of thousands or millions of years of evolutionary history are wiped out. A unique genetic code is deleted. A special spirit is annihilated.

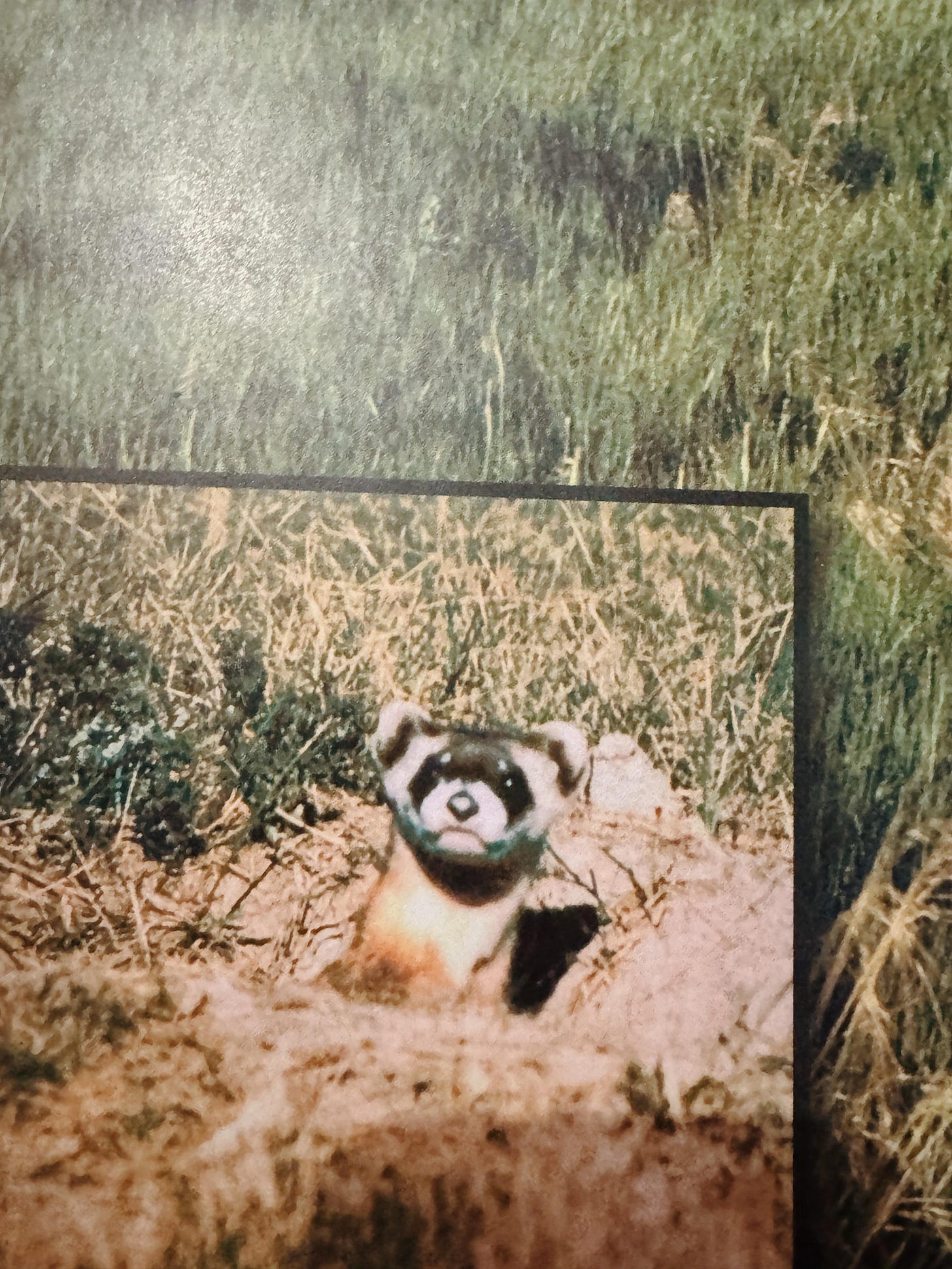

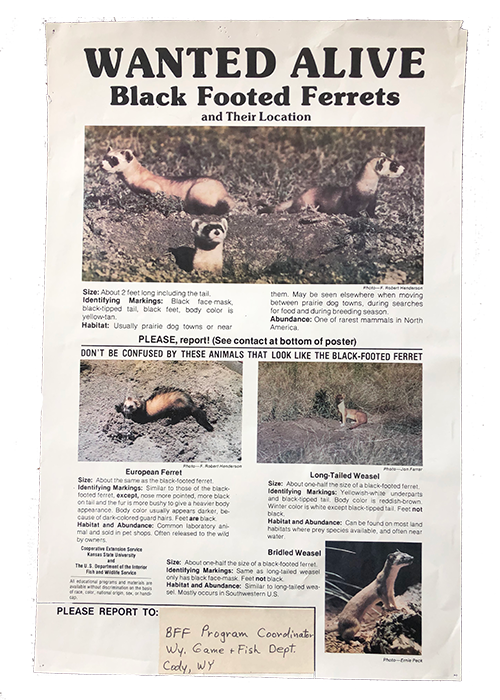

Such was believed to be the fate of the only ferret native to North America, the black footed ferret, Mustela nigripes, when the last one died in captivity in 1979. But to steal the words attributed to Mark Twain, the reports of their death as a species turned out to be greatly exaggerated. Two years after they were thought to be extinct, in 1981, a ranch dog named Shep brought home a dead ferret to his owners, John and Lucille Hogg, who lived near Meeteetse, Wyoming. You’re a good boy, Shep, even if you may have killed one of the last remaining ferrets on earth, you’re still a good boy!

The Hoggs then reported the discovery, leading to the identification of one surviving wild population of around 20 black footed ferrets. Scientists swooped in and began a captive breeding program, which was moderately successful, bringing the ferrets back to some of their ancestral lands in Wyoming, Montana, and South Dakota. Today, about 400 wild black footed ferrets are prancing on Earth.

We towed our Airstream to Badlands National Park with a mission to find one of these cute little predators. But first, we needed to understand the behaviors of their arguably even cuter prey, the prairie dog, whose own demise is the reason black footed ferrets found themselves on the brink of extinction. Prairie dogs, which are not in fact dogs, are an herbivorous burrowing ground squirrel that make up 90% of the ferret’s diet. We went to one of several establishments outside the park where you can buy a bag of peanuts to feed these little guys and get close-up videos like this one.

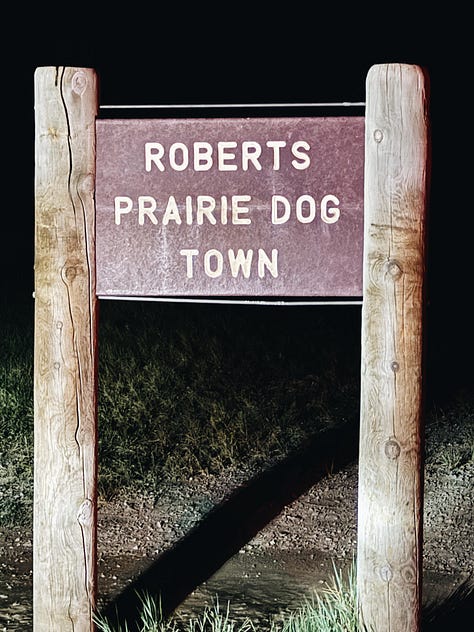

After watching prairie dogs play and eat and wondering how many peanuts they can eat before exploding, we were ready to find wild ferrets. We went to the Ben Reifel visitor center and got to meet with a young, long-haired male ranger who was the resident expert on the ferrets, despite the fact that he is yet to see one in the wild. He said he’d gone on 6 expeditions with biologists to find them and had struck out every single time. But he said that while it is unlikely to find one, it is possible, and circled 3 places on the map where they were more likely to be, including a place called Roberts Prairie Dog Town. He told us to use our headlights to scan the prairie, looking out for two green neon lights close together, which are the ferret eyes.

We left the campsite just after sunset, which was around 9:30 pm. The kids all had their warm clothes on, headlamps in their packs, and full bellies. Despite having the odds stacked against us. We were excited for another “night adventure” to try and encounter an animal that, honestly, none of us even knew existed a few months ago. We loaded everyone back in the truck in search of these rare polecats and drove off into a pitch black night in the Badlands.

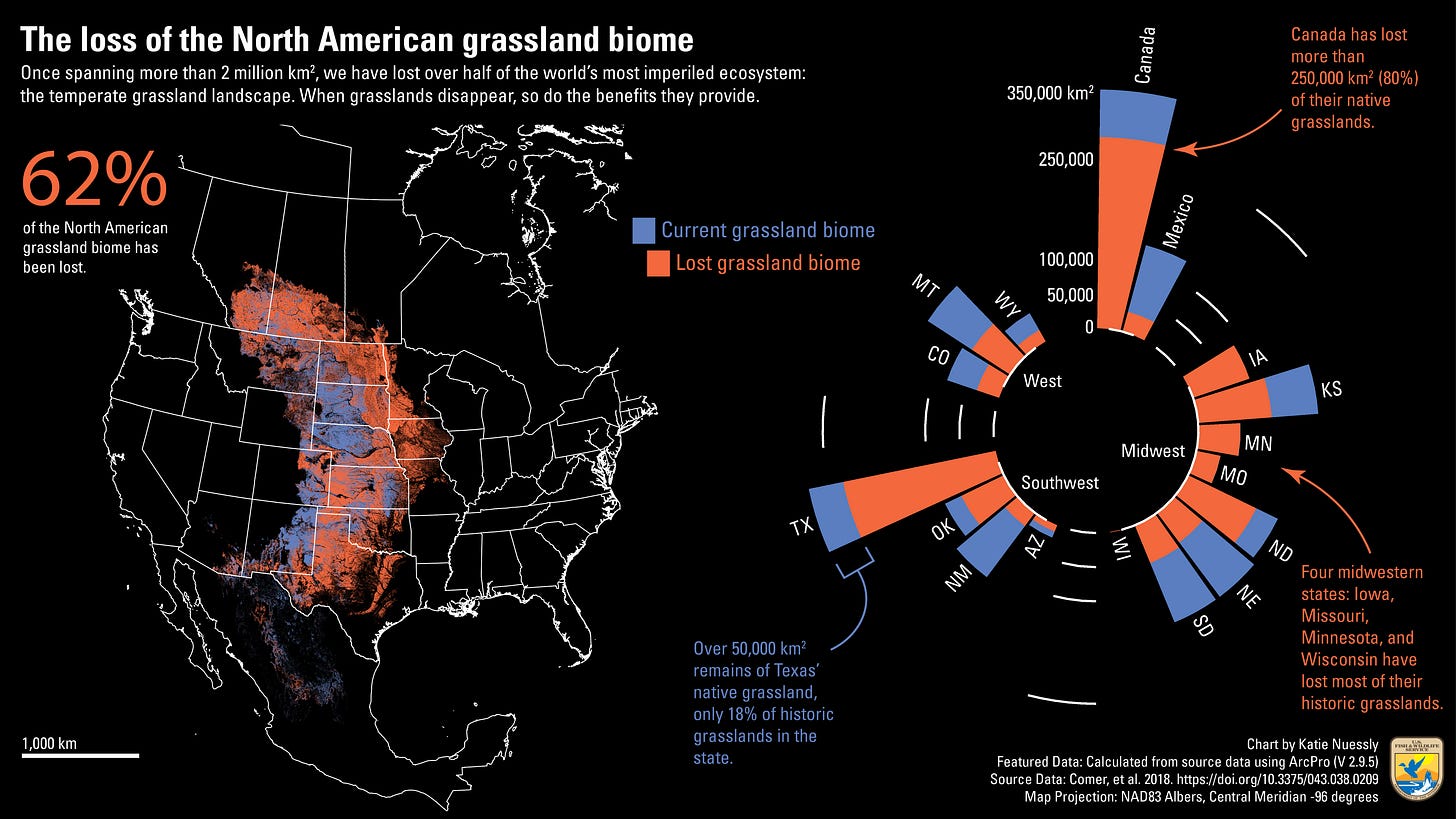

To understand why black footed ferrets are nearly extinct, you just need to look at this graphic below. The traditional grassland biome known as the “prairie”, stretching from Northern Mexico into Canada, was about 600 acres before the Europeans. Today, due to plowing for crops such as corn, wheat, and soybeans, cattle grazing, and urban expansion in America’s “heartland”, the prairie is now only about 100 acres in size and is highly fragmented and degraded.

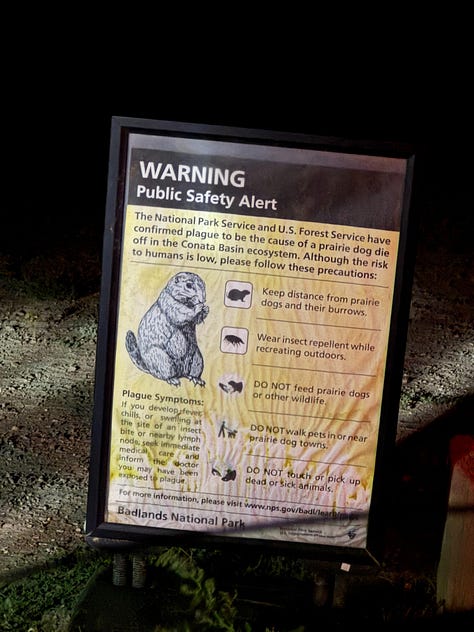

The decline of the prairie has meant the decline of prairie dogs, the ferret’s primary food sources, which are widely considered an agricultural pest. And so, as 95% of prairie dogs and their grassland habitat was eliminated, too went the black footed ferret, which needs about 100 acres of prairie habitat for a single ferret family to survive. Additionally, both prairie dogs and ferrets are highly susceptible to sylvatic plague, a bacterial disease introduced from Asia, which has devastated many remnant populations.

Today, about a third of the entire population of black footed ferrets call Badlands National Park home, and when we read about the plight of these cute little guys, we decided that we had to drive through their territory to try and find one of them. We knew the odds would be low, but we wanted to give it a shot.

The turnoff towards Roberts Prairie Dog Town led us down an empty, bumpy dirt road, with burrows bulging up randomly on the surface of the ground like acne on a teenager’s face. The mounds seem to stretch as far as the eye can see. At first, we couldn’t see anything, but eventually we spotted a couple of prairie dogs, and next to them were a pair of very small burrowing owls hanging out along the edges of a mound. With no sign of the ferret, we kept on driving slowly and on high alert. The kids were climbing into the front seat. We drove for about another 30 minutes and never spotted the ferrets. We decided to turn around to take a picture of the sign, and when we came upon the sign, Dana spotted two green lights. She alerted everyone to try and be very still and quiet, not an easy task for this crew, but they obliged. We took a closer look, and when it turned, it was not a ferret, but it a big-horned sheep right there staring back at us. Everyone was still very excited.

We explored all 3 places the ranger mentioned, keeping our eyes peeled closely to the side of the road, realizing that wildlife was everywhere. Now and then, one of us thought we saw it, but nothing conclusive. Dana spotted another new animal that was very cleverly camouflaged with the grass on the side of the road. “It’s a porcupine!” she exclaimed and made Jaron reverse the truck. Nobody believed her, but as we approached, Jaron stepped out of the car and confirmed it was indeed an extremely well-hidden porcupine. How did she see that? Another new animal to add to our bio list. There was a lot of hoopla around the porcupine, too, but sadly, no sign of the black footed ferret.

We knew that seeing endangered species in the wild would be quite a challenge. And realized that while spotting these creatures and having a real encounter with them is certainly a great goal to have, the thing that matters more is the attempt. It’s having the thought in your head to see these creatures. Talking about them, writing about them, keeping them top of mind in a world whose priorities lie elsewhere. It’s a contrarian idea.

But for our family, going out and looking for ferrets that night with our kids in our truck was the recipe for a most memorable night. Our kids will never forget the animals we did see, and the feeling of anticipation when the headlights of the truck bounced off two green little lights.

Could it be the black footed ferret?

We didn’t see the ferret that night, and the next night we had to leave the Badlands as we couldn’t reserve a spot for longer. We had to move on, and we were at peace with it.

It made us understand that our family's mission of encountering 73 threatened species may be the right one; it’s not the encounter that matters most. It’s the attempt. It’s keeping alive of this creature alive in our minds. The thrill of going out into the bush and never knowing what you’ll see. We may never see a black footed ferret in the wild, and that’s ok. We are proud of our effort and putting ourselves in the right place to get lucky. 2 out of 3 kids fell asleep on the way home. The next day, we bought a black footed ferret stuffed animal at the visitors’ center. That may be the closest we’ll get to a black footed ferret this time.

And don’t miss this interview with John Hogg talking about Shep, the legendary ranch dog!