73 and We

Here's why that number matters to us

Our family quest is to try to encounter 73 threatened animals and plants in the wild. It functions as a north star for us, guiding us as we go out to explore this vast planet. There are so many incredible places to visit that we could spend the rest of our lives traveling and still not see them all. As we venture away from the comfort of our home, it feels critical to have a very clear purpose, some measure of order in the chaos, a compass.

In many ways, we’re continuing and expanding our kids’ education. Our older kiddos currently learn through these epic quests at school. Every semester, a different theme becomes their major focus, in which they dive deep into an area of study. They have to come up with a creative project they will showcase to the whole school at the end of it. One quest, for example, was game creation, where they invented their own board games. Another was about architecture, where they built models for structures. Another was about primal survival, where they learned how to start fires with a flint and steel. So this is a family quest about wildlife, given that this is a subject that has consistently fascinated our children and us. And we are going on the greatest field trip imaginable. We will learn and be curious together.

So why the number 73?

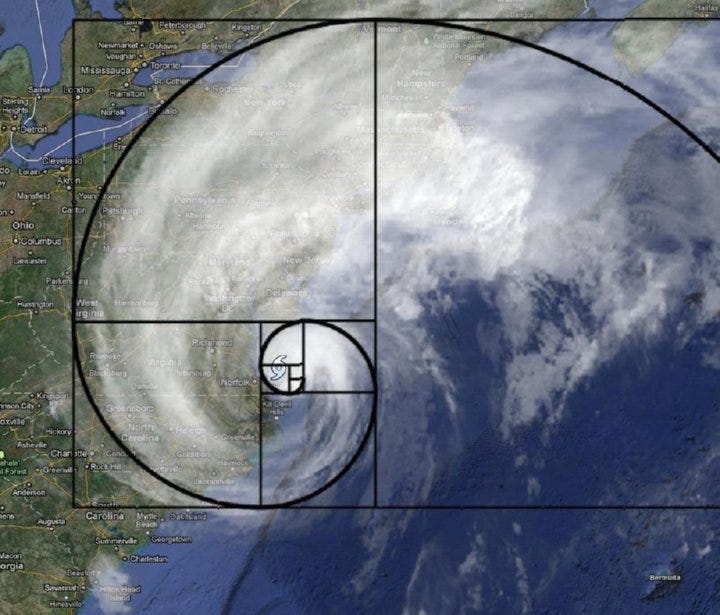

The Fibonacci sequence and related golden ratio, the magical set of numbers (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89…) encoded geometrically in the spiral pattern on Nautilus snail shells, hurricanes, and sunflowers, inspired Earth Parade’s snail shell icon. However, 73 is not a Fibonacci number, so that is definitely not the reason.

It’s not because, according to numerology, the number 73 is a vibration about creating ingenious and innovative things to improve the world. Or because it’s the 21st prime number.

It’s not an ode to the year 73 BC, which seemed like a great year, considering it was God’s Jubilee. Or because of the year 1973, which wasn’t a particularly great year, considering it brought the world an oil crisis, a recession, and another deadly war in the Middle East.

No. It wasn’t because of any of these things.

We picked 73 because of an alarming statistic.

A data point that we couldn’t shake.

In the 50-year period from 1970-2020, the average size of wildlife populations fell by a staggering 73%, according to the World Wildlife Fund study of more than 5,000 vertebrate species of amphibians, birds, fish, mammals, and reptiles across every world continent.

Poof. Just like that. 27 out of 100 animals are still here. The rest are gone forever.

A 2019 United Nations report found that about 1 million species face extinction in the coming decades, with the global rate of species extinction tens to hundreds of times higher than the expected background rate. Humans are responsible for poaching, logging, polluting, overfishing, overdeveloping, and overheating this planet. We are facing the sixth major extinction event in Earth's history, and the only one caused by a single species.

The worst losses occurred in Latin America, with a shocking 95% loss of vertebrates. Carajo, that’s nearly 100%. Freshwater species experienced the greatest decline, with more than 85% of wildlife disappearing over just five decades. Rivers, lakes, and wetlands are not the pristine places they once were. There is pollution (with unspeakable levels of plastic and microplastics), fragmentation (which is a fancy way of referring to dams and other ways to divert water sources), and unsustainable water use, endangering species such as river dolphins and freshwater fish.

The study is based on what’s called the Living Planet Index (LPI), which measures wildlife population trends using time-series data from more than 35,000 monitored populations. This is the largest scale study of its kind, but of course, it leaves out the vast majority of wildlife populations. That said, it’s an important biodiversity indicator, and we can assume that unstudied wildlife faced a similar decline. While it doesn’t include invertebrates or plants, we can conclude that they, too, are facing similar declines.

Not surprisingly, countless species have gone extinct in this period. Faramea chiapensis, a medicinal Mexican plant species lost to deforestation, was declared extinct in 2020. And then there’s the Jalpa False Brook Salamander (Pseudoeurycea exspectata), pictured below in what we’re told is the only one ever photographed and the only one we will ever photograph since it was declared extinct in 2019 due to habitat loss in Guatemala. Chinese paddlefish (Psephurus gladius), last seen in 2003, was declared extinct in 2022 due to overfishing and the construction of two major river dams. Thanks to poachers and habitat destruction in Africa, we have lost forever the northern white rhinoceros, with only two animals remaining in captivity, and unfortunately, both are female.

The list of species we’ve lost over the last five decades is long and gaining traction. At the rate we’re going, it’s not hard to imagine what planet Earth will look like in another 50 or 500 years. The current trajectory is that we human beings will be the first known species in the universe to destroy the majority of natural systems on our home planet, replacing everything with this new synthetic proxy planet. Are we being alarmist? We don’t think so. The data and anecdotes both point to a world that is more devoid of wildlife than the one we’re currently living in. The principal question we should ask ourselves is: Is this the kind of world we want to leave for future generations?

Our children have always been obsessed with wildlings of all kinds, and we feel like we have some kind of duty to show them as many of them in their natural habitats as we can while we can. While doing so, we hope to raise awareness for this grim metric that has become a symbol of the extinction crisis. Our kids are young, precious, and precocious, so this will be a challenging quest. Our top priority will always be their health and safety. Our next priority will be maintaining this humble newsletter, whose founding inspiration may, in fact, originate from watching and reading The Lorax a gazillion times. The children’s book written in 1971 was Dr. Seuss’s own favorite and as prescient as any other he wrote, and maybe in the whole genre. Tragically, in the non-Seussian, nonsensical real world we all live in, there is no Lorax whose job it is to speak for the trees “for the trees have no tongues.”

We believe that sharing the stories of these threatened plants and animals will help us get a more complete picture of humanity and the consequences of human civilization. Their histories and destinies unfold as a mirror of our own. Their futures and ours are inseparable.

This isn’t a bucket list trip. It’s a trip of giving. To the earth. To our family. To our own hearts and minds. We want to celebrate those life forms hanging in there, whose future and fate will ultimately depend on human (read: our) decisions. This project is an act of hope that humanity will come to understand the tradeoff we are making deeply and radically change course.

So that’s where the number 73 comes from.

“Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot,

Nothing is going to get better. It's not.”

― Dr. Seuss, The Lorax